When it comes to urban political ecology and Mexico City in academic literature, there is no doubt that water is the most written about topic in the literature. The rapid processes of urbanisation over the past 700 years have turned Mexico City from a city of floating gardens and a place that was once dubbed “The New Venice”[1], into a sprawling urban metropolis which has to pump water from up to 120km away to fuel its water needs. The topology surrounding Mexico City also adds a significant challenge to meeting the city’s water demands as well as the region being prone to earthquakes. Since this is such a big issue to explore in Mexico City, I will be splitting the topic into 2 separate blog posts. This post tackling indigenous populations at the start and end of the Mexico City’s water flow, and the next one about transportation and distribution of water in Mexico City. To help explore the urban political ecology of Mexico City’s water in this blog post and the next one, I am going to look at these issues through the lens of ‘urban metabolism’ (what happens to resources from their entrance to their exit in a city). This YouTube clip from the UN will help to get a basic understanding of what urban metabolism is:

Where does Mexico City’s water come from?

The demand for water in Mexico City has far reaching impacts, starting at the source of the water with the local indigenous populations. Although this blog is about Mexico City, it is important to acknowledge the impact on all actors involved in the production and reproduction of the city’s urban environment. This importance is highlighted by “a review carried out nationwide in Mexico between 1990 and 2002 of some 5,000 newspaper articles on water conflicts found that 49% of them took place in the Valley of Mexico”[3].

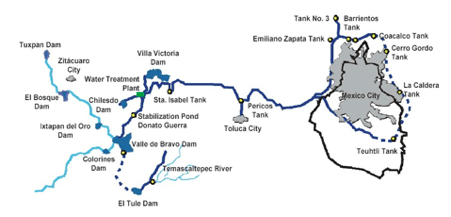

Mexico City gets 30% of its water via the Cutzamala reservoir system, starting some 120km from the Federal District in Mexico City [2]. The first dam in the system is the Villa Victoria dam (seen on the map below), which is run by the National Water Commission (NWC).

As mentioned in earlier blog posts, Mexico is home to 62 indigenous groups. One of whom, the Mazahua, have been heavily impacted by the capital’s demand for water. The Victoria dam especially has changed the Mazahua’s natural habitat from one of nature and beauty to one of barbed wire and concrete [4]. The Mazahua have also been left with very little water due to the greed of the National Water Commission and the needs of the capital, leaving some households only receiving water through a hose once per week. The actions of the NWC have also meant that the land is extremely dry as all the underground water is being siphoned off, and that wildlife which the locals depend on such as fish are less prominent. The Mazahua have held numerous protests, including a 15-day stand-off a nearby sanitisation plant in order to demand that they all receive potable water on a daily basis. These conflicts caused the emergence of the Mazahua Women’s Army in Defense of Water who gained press notoriety after leading numerous protests.

The case of the Mazahua is an example of how Mexico City’s demand for water is met, but at the expense of the quality of life in rural areas.

How water leaves the city

At the other end of the chain, are the areas who are the recipients of Mexico City’s wastewaters, all the so-called ‘blackwater’ that has been used to treat sewage amongst other uses. The physical elements make disposing of this blackwater challenging, instead of a natural exit it has to be pumped through 11,000km of pipes and sewers [5]. However, new infrastructure is being invested in by the government as well as Mexico’s richest man, Carlos Slim. Of particular importance is the new treatment plant in the Tula Valley (pictured below). Although there is conflict in this situation again, as local indigenous populations (which I look at in blog 7) believe that their home is being used as a dumping ground for the city’s waste. For years the local indigenous population’s land has been used to dump waste, which they have tried to use to their advantage by crowing crops using the waste as a fertiliser.

In an ironic but also dangerous twist health-wise, these crops are often sold back to Mexico City residents [6]. Despite protests and the water company’s assurance that the new plant will improve the situation, the local population are not as certain. It is clear that water demand in Mexico City has affected the poor the most at all parts of the cycle. However, the government and water companies are making attempts to help alleviate these inequalities but face significant environmental barriers as well as numerous social and political issues.

Here are the references I used:

[1] Watts, J. (2015) ‘Mexico City’s water crisis – from source to sewer’, (WWW) Guardian: London (www.theguardian.com – accessed 14th February 2020).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Jiménez Cisneros, B., R. Gutiérrez Rivas, B. Marañón Pimentel and A. González Reynoso. (eds.). 2011. Evaluación de la política de acceso al agua potable en el Distrito Federal. Mexico: PUEC-UNAM.

[4] Delgado-Ramos, G., (2015) ‘Water and the political ecology of urban metabolism: the case of Mexico City,’ Journal of Political Ecology, 22(1), pp.98-114.

[5] Watts, J. (2015) ‘Mexico City’s water crisis – from source to sewer’, (WWW) Guardian: London (www.theguardian.com – accessed x February 2020).

[6] Ibid.