In the Western contemporary, sanitation is a given. For the entirety of my life, access to fresh drinking water and clean loos, supported by a well organised sewage system has seemed like a basic function of modern existence. But for the non-white communities in Cape Town’s informal settlements, my everyday reality would be their ‘dream come true’. This blog will cover the origins and ongoing legacy of another urban metabolic flow subject to fragmented access in Cape Town: sanitation.

This environmental injustice harks back to a time before the days of Apartheid. In 1900, the bubonic plague arrived in Cape Town, prompting English administrators to act fast. They pounced on pre-existing fears over the hygiene of nonwhite neighbourhoods, forcibly relocating these communities to Cape’s peripheries. This displacement was their attempt at sanitising communities, with no efforts made to improve access to healthcare, hygiene or living standards. Isolation was another historical example of Cape Town’s nonwhite communities being cast out and laid to waste.

The epidemic was arguably seen as an opportunity by white rulers at the time, as they employed medical terms to justify racially-motivated territorial segregation. The ‘Sanitation Syndrome’ was coined by Swanson to reflect this conflation of race and disease; an unjust, immoral and utterly false accusation (1977). In fact, more whites were victims of the outbreak than black people, but of course the political monopoly was able to distort data to favour the former and relegate the latter. So, with over a century past, has the syndrome lived on?

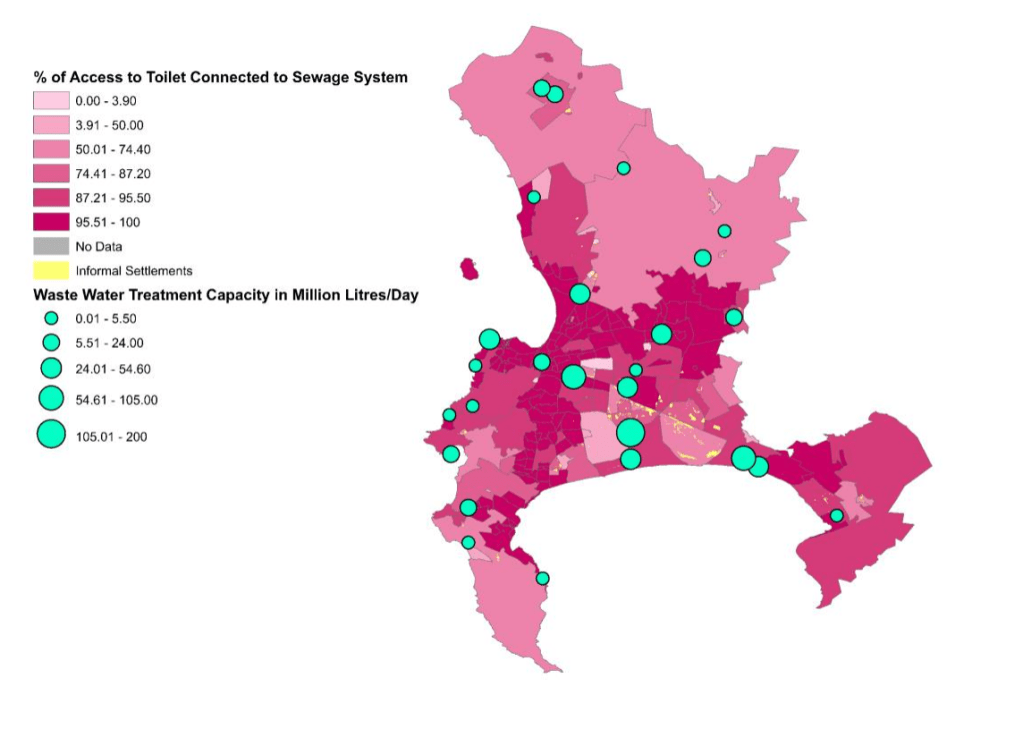

Unsurprisingly, yes. A recurring theme in my blogs has been the unevenly distributed (or lack of) infrastructures of social and ecological services in Cape Town. Sanitation represents yet another segment of the city’s metabolism that Townships have been disconnected from in yet another act of environmental racism. Figure 1 visualises this isolation, with informal settlements predominantly residing in regions unsupported by the municipalities sewage system. Sanitary negligence has led to a hotbed of disease, including dysentery, cholera and diarrhoea. The injustice is three-fold: sanitation is a basic human right, access is racially bound and the diseases are preventable.

“Bursting for the loo” and “dying for a wee” are figures of speech used light-heartedly in colloquial Western discourse. But this is no joke for Cape’s Townships. With no sewage infrastructure, residents have no access to household loos, instead relying on porta potties and chemical toilets, which are limited and located far from the majority of people’s homes. Making matters worse, public toilets are hotspots for predators. Researchers at Yale University developed a model that estimated 635 sexual assaults took place on average every year between 2003 and 2012 at the Khayelitsha Township. Women and children are particularly vulnerable, highlighting that Cape Town’s inequalities are not limited to just race, but can also be understood in terms of gender and age. Figure 2 spotlights this unfortunate case of child geographies, with a youth playing amongst a sewage infested and trash laden stream of water.

By using UPE’s analytical framework, Cape Town highlights the uneven impacts of contaminants entering an urban metabolism. The blog has highlighted sanitation as yet another function of Cape Town’s urban ecology that is inherently politicised. The socio-technical revolution was kept from the black demographic who were wrongly conflated with an imagery of disease. These false, racially motivated sentiments later materialised into an urban design built on displacement and segregation. Sanitation is commonly referred to as an ‘invisible infrastructure’, but amongst Cape’s Townships, it is simply non-existent and represents a vestige of Apartheid planning in need of eradicating.

List of References:

Currie, P.K., J.K. Musango, and N.D. May. 2017. Urban metabolism: A review with reference to Cape Town. Cities 70: 91–110.

Swanson, M. W. (1977) “The Sanitation Syndrome: Bubonic Plague and Urban Native Policy in the Cape Colony, 1900–1909”, The Journal of African History, 18, 3, 387-410.

Totaro, P. (2016) “ Dying for a pee – Cape Town’s slum residents battle for sanitation” (WWW) Cape Town: Reuters (https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-safrica-slums-sanitation/dying-for-a-pee-cape-towns-slum-residents-battle-for-sanitation-idUKKCN12C1IK; 22 February 2020).

UN (2019) “Eight things you need to know about the sanitation crisis” (WWW) New York: United Nations (https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/10/eight-things-you-need-to-know-about-the-sanitation-crisis/; 22 February 2020).

It seems as though the uneven sanitation in Cape Town is pretty historically rooted with not many signs of improvement. Interestingly in Mexico City, the government made legislation making it a mandatory requirement for landlords to provide sanitation. Of course, with the informal settlement it would not be clear how similar legislation would be implemented. Especially as it appears the SA gov. do not have any plans to turn things around.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this post.

Epidemic and disease have often been a trigger for improvements of the sanitation system. It is striking to see that nothing is done to improve sanitation in Cape Town’s informal settlements while the apartheid is supposed to be over and that other neighbourhoods profit of efficient sanitation systems.

LikeLike