Mexico City was named in 1992 by the UN as the “most polluted city on the planet”[1], however it is trying to shake off its prior reputation as a smog and soot filled city. A narrative which has been at the forefront of this attempted change is from changing Mexico City from grey to green. Green spaces in Mexico City have historically been an interesting case study from an urban political ecology perspective given the significant uneven distribution of green spaces across the city’s boroughs. Investigating how these spaces are produced, who benefits and loses, and who are the decision makers in this process are very interesting questions in the case of Mexico City. This blog post aims to answer these questions in relation to the city’s green space and will depict the deep-rooted influence of Mexican political economy as an agent for the institutionalisation of green space policy in Mexico City. I will finish by showing how Mexico City is opening up alternatives to private funding and fighting against privatisation of green spaces.

Despite consistent efforts by socio-environmental institutions in Mexico City to address as the uneven distribution of green spaces, they are still held back by financial dependence on private funding sources. Privatisation of green spaces in Mexico City has a worrying trend attached whereby the space is gentrified and segregated from minority populations[2]. However, a positive trend are the alternatives to private investment in green spaces in Mexico including the creation and maintenance of green spaces involving social participation. The Mexican government endorse ‘Eco-city’[3] projects such as the “Via Verde” to essentially create new green spaces in the urban environment however many inhabitants believe efforts like these are metaphorically and literally a façade to distract from the lack of public green space.

The creation of green space has been the focus of nature/ society debates amongst the Mexican population since 1840 when the city mayor ordered the planting of vegetation on the Plaza Mayor’s periphery (currently known as Zócalo) to make for a better public space to walk and rest[4]. Zócalo still holds this tradition with trees around its periphery to this day as shown above. This bit of history brings to the forefront a very relevant topic in Mexico City surrounding who produces and manages green space. Private funding holds an iron-grip on many of Mexico City’s green spaces, as shown recently with the unexpected privatisation of two parks in Mexico City’s Distrito Federal.

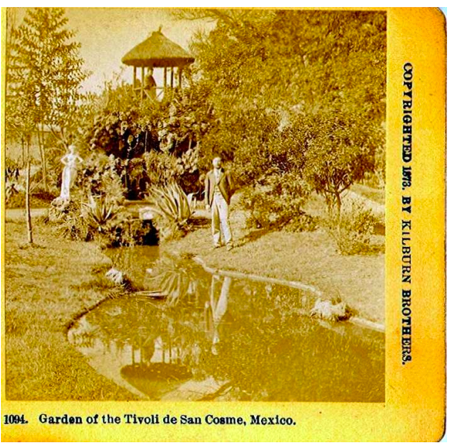

Historically, green spaces have been managed and funded by private managers, often from foreign sources such as beer and tobacco companies during the latter stages of the 19th century [5]. These companies kept these parks for the exclusive use of the city’s rich, and they were always situated in wealthy suburbs, laying the foundations for the uneven distribution of green spaces in Mexico City. Often these green spaces would be without a single indigenous person in sight. An example of these parks is shown in this image below from 1873.

This is a clear answer as to which party loses out in this situation. However, has this segregation carried on into the current day and age? The answer is yes, and even more green space is being privatised. Often this green space is developed into housing, and subsequently uses some green space as a private garden for the residents of these new builds.

Despite this negative scenario, the creation of decentralised government offices such as the PAOT (Environmental and Land Management Agency) is helping to fight for the Mexico City dwellers against privatisation. PAOT provides locals with the legal toolset to defend their environment against privatisation. However, the PAOT is still not operating at its best capacity due to the lack of public knowledge and access to its facilities, not helped by its office location in an affluent area of the CBD. This means that although they do good work, such as “the successful constitutional amendment they proposed to safeguard collective environmental needs”[6], they need to do more to reach the most marginalised populations. There is a general consensus that there needs to be a move towards a more bottom-up decision-making process. Education projects such as the Centro de Agricultura Urbana Romita help to educate residents on how they can produce and manage their own green spaces on their rooftops in the city. With a rise in the number of these small-scale and local projects, alongside government branches like PAOT, Mexico City’s marginalised populations have a chance of enjoying some green space of their own.

Here are the references I used:

[1] Centre for Public Impact (2016) ‘Mexico City’s ProAire programme’, (WWW) CPI: USA (www.centreforpublicimpact.org -accessed February 1st 2020).

[2] Alvarez, R. (2015) ‘Urban political ecology of green public space in Mexico City: Equity, parks and people’, (Doctoral dissertation, Arizona State University).

[3] Caprotti, F. and Romanowicz, J. (2013) ‘Thermal eco‐cities: Green building and urban thermal metabolism’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(6), pp.1949-1967.

[4] Sorenson, M.G., Keipi, K.J., Barzetti, V. and Williams, J. (1998) ‘Manejo de las áreas verdes urbanas’, Inter-American Development Bank, Sustainable Development Department, Environment Division.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Alvarez, R. (2015) ‘Urban political ecology of green public space in Mexico City: Equity, parks and people’, (Doctoral dissertation, Arizona State University).

[7] Vitz, M. (2018). A city on a lake: urban political ecology and the growth of Mexico City. Duke University Press.

Really poignant blog post on the dangers of green urbanism Will! I am a big fan of what has been described as ‘Biophilic urbanism’, which essentially reintegrates nature into our built environment in an attempt to bring harmony back to the human and natural realms. However, as your blog clearly articulates, this genre of urban planning and architecture could lead to a kind of ‘green gentrification’ that excludes less privileged communities. Collective action and social participation are sources of remedying this exclusivity and something I raise in one of my blog posts (https://uclupe.design.blog/2020/02/03/reclaiming-urban-ecologies-through-collective-action/).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found your post really interesting. I did not even imagine that key public spaces like parks could be privatised.

I think it is a duty of municipalities, especially for big cities, to make green spaces available for the comfort of all their citizens. But it is much more important for a polluted and warm city like Mexico City. Asides from absorbing carbon, vegetation could help to reduce urban heat island (UHI) and reduce air pollution. Even if it is privatised, maybe the Via Verde project can be interesting to reduce pollution directly from the road.

I hope the situation will improve thanks the initiatives you present at the end of your post. It would be interesting to see if they are also a mean to introduce or reinforce urban agriculture in Mexico City, which have plenty of benefits.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing your ideas Will! I think your argument of implicit social exclusion underlying projects such as the ‘Via Verde’ is really resonant, and an issue experienced by a lot of residents of other cities. I’m really glad you’ve brought this up; aside from the benefits green spaces can provide for tourism, health and a better urban experience, it can also be a source of divide and conflict. And this discord is central to fuelling bodies like the PAOT to enact collective change. Hopefully, marginalised residents can also enjoy green spaces to their fullest extent. Anything is possible!

LikeLike