Mexico City has a very complex dilemma between the housing needs of a rising population and environmental conservation. Obviously, this is not an uncommon situation in this day and age with the majority of large urban cities experiencing urban sprawl to some extent. A prime example being London, right on our doorstep, which has its own issues involving green belts and urban sprawl (see this interesting article for more information). Mexico City’s housing and conservation situation is arguably much more complex. First, attention needs to be paid to the history of working-class settlements to establish how this situation arose. Secondly, I will explore land tenure regulation and ecological conservation in Mexico City more generally. Before going into more detail on urban policy and informal settlements in the conservation area of the Federal District in Mexico City.

Brief history of informal settlements issue

Mexico City has 867 informal settlements, comprising of around 51,000 households as of 2010, so the number now is likely to be inflated further [1]. Working class settlements, referred to as the ‘embarrassments of Mexico’ by the upper classes, have historically been characterised by poor infrastructure and sanitary conditions [2]. A lack of drainage, drinking water and paved streets made for ideal breeding conditions for malaria and gastro-intestinal related health issues. The government recognised these issues in the 1930s and set about attempting to solve these issues. Firstly, they revised their building code for current and future buildings to make it a mandatory requirement for each housing unit to have a toilet and water connection. This caused considerable friction between property owners and government regulators, over the costs which were estimated to reach 127 million pesos to ensure each unit was up to standard [3]. The state held property owners to these regulations, but this had unintended consequences whereby rents increased and forced renters to move out as they couldn’t afford the rent increases. The state even started its own housing projects such as the one pictured below, but they never really made a real dent in the battle against sanitary and housing inequality.

Land tenure regulation and ecological conservation

Land regularisation became commonplace in informal housing settlements in Mexico from the 1970s onwards [6]. The government supported regularisation, and this encouraged informal urbanisation. However, this has increased the privatisation of lands taken over informally which may have previously been socially owned. As a result, informal housing settlements have expanded and has inadvertently protected the illegal property market. Mexico City’s communal land has since been largely taken over by informal settlements [7].

Many of these informal settlements are on ecologically valuable land, not designed for urban developments. This is where the dilemma really lies. There is mounting social pressure to conserve these areas alongside an ever-increasing demand for housing and service infrastructure. The government have tried to implement forms of zoning such as cyclone barriers in the South of the city to try and depict strict borders, yet sprawl is still occurring. Ecological degradation is considerable when informal settlements set up camp given the poor service infrastructure such as the issue of raw sewage being released with no treatment or containment, which has been a problem since the earlier 1900s. Due to illegal land occupation playing a huge role in political and social legitimacy, local authorities would lose a lot of support if they were to take drastic action.

The Federal District

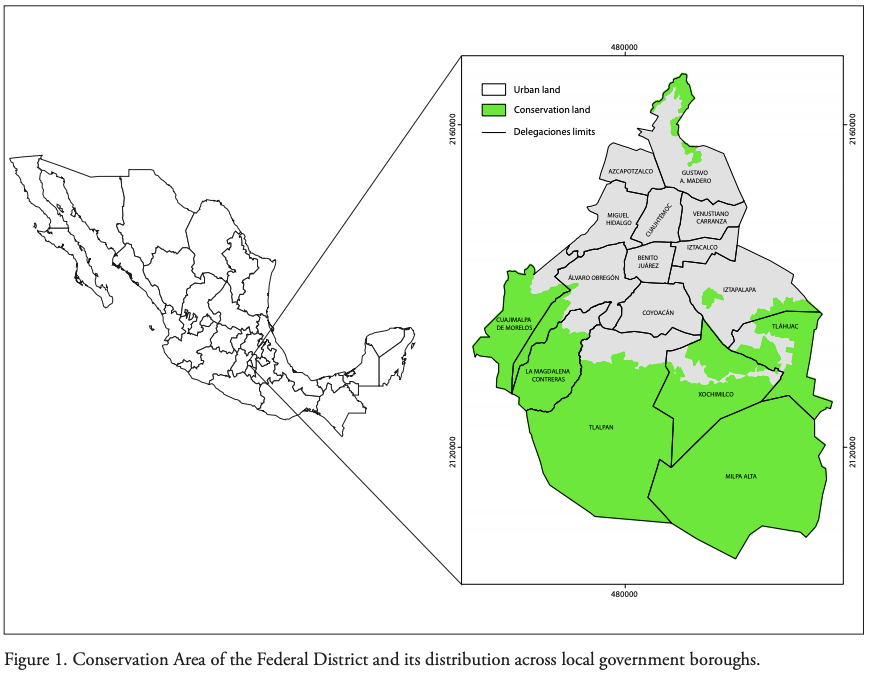

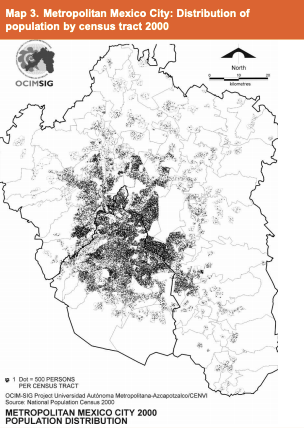

The Federal District contains what is called a ‘Suelo de Conservación’ which roughly translates to ‘Conservation Land’ and has a population density of roughly 12,700 per km2 [5]. The British equivalent would be land protected under a city’s green belt, or potentially at a lower scale just a ‘greenfield site’. Within this Conservation Land is a sub-zone called the Preservation Zone which comprises of 59% of the Federal District’s land (see image below). The purpose of this preservation zone is to have a portion of land which is extremely regulated by environmental conservation rules to protect its biodiversity. The area contains over 1800 plant and animal species along with an aquifer feeding 57% of the Federal District’s water consumption. Wooded areas help to handle CO2 fixation and oxygen production, and the area is also key for ecotourism.

However, this biodiversity is compromised by the illegal takeover of land for informal housing settlements, compare the two maps above for example and one can see how population density is encroaching on the conservation land. Informal settlements mean a clearing of woodland and polluting of this crucial aquifer. One might jump to the conclusion that the area is clearly not regulated enough if informal settlements can pop-up seemingly without much opposition. In reality it is in fact the opposite! The conservation zone is over regulated, causing a lack of coordination within government factions and a fragmentation of actions on these settlements meaning nothing gets done [10]. Compounded by unclear legislation directly relating to informal settlements are Mexico City has arrived at this current scenario whereby the conservation area is slowly being eaten into by informal housing settlements.

When looking at this problem, it makes sense to analyse why is there such a large presence of informal housing in the Federal District. During the 1990s the government continued with building social housing; however, it was aimed predominantly at middle and low-class formal workers as opposed to informal. Besides this initial problem, the Federal District had no reserve of available land that they could build on anyway. Hence why these informal settlements are attracting more and more occupants because there is a lack of alternatives for many of the aforementioned population. Urban and environmental policy in the Federal District has failed to address the problem of informal housing settlements, meaning that the ecological problems which come with these settlements are bound to continue until radical change is brought about. Continued land regularisation by the government will only exacerbate this issue and fragment the conservation area in the district further. The political risk to address the issue means that it will continue to go avoided in political decision-making. Who knows what the future holds for Mexico City’s other conservation areas?

Here are the references I used:

[1] Delgado-Ramos, G. C., & Guibrunet, L. (2017). Assessing the ecological dimension of urban resilience and sustainability. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 9(2), 151-169.

[2] Vitz, M. (2018). A city on a lake: urban political ecology and the growth of Mexico City. Duke University Press.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Delgado Ramos, G. (2019). “Real Estate Industry as an Urban Growth Machine: A Review of the Political Economy and Political Ecology of Urban Space Production in Mexico City,” Sustainability, MDPI, Open Access Journal, vol. 11(7), pages 1-24, April.

[5] Delgado-Ramos, G. C., & Guibrunet, L. (2017). Assessing the ecological dimension of urban resilience and sustainability. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 9(2), 151-169.

[6]Aguilar, A. G., & Santos, C. (2011). Informal settlements’ needs and environmental conservation in Mexico City: An unsolved challenge for land-use policy. Land Use Policy, 28(4), 649-662.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Saavedra, Z., Revah, L.O. and Barrera, F.L., (2011) ‘Identification of threatened areas of environmental value in the Conservation Area of Mexico City, and setting priorities for their protection,’ Investigaciones Geográficas (Mx), (74), pp.19-34.

[9] Connolly, P., (2003) ‘The case of Mexico City, Mexico,’. Case study report prepared for Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Urban Report.

[10]Aguilar, A. G., & Santos, C. (2011). Informal settlements’ needs and environmental conservation in Mexico City: An unsolved challenge for land-use policy. Land Use Policy, 28(4), 649-662

Really interesting post! However, this raises some really important questions over what happens next. It’s very difficult to appease everyone with the right policy; enforcing the ‘legality’ of land governance will cause exclusion of certain communities, whilst allowing informal settlements to expand will create ecological and infrastructural problems, reinforcing divisions/binaries that already exist (as mentioned in your other post about green space).

LikeLike