Waste in Mexico City is a fairly under-researched area in urban political ecology literature despite being extremely interesting when analysed under the microscope of urban metabolism. Inspired a lecture on waste and ‘circular economies’ , it makes sense this week to look at these topics in Mexico City. From a UPE standpoint, looking at urban metabolism can reveal how waste flows transcend institutional and geographical boundaries and in turn shed light on the intricate layers of infrastructure and land use in a city[1]. Although waste in Mexico City has not received much UPE attention, it has certainly garnered the focus of media outlets [2,3] with articles every month on the topic. A question posed within the aptly named ‘Global Political Ecology’ is whether waste is concomitant with progress? It is worth keeping this question in mind whilst reading this post! Mexico City hits the headlines for both positive and negative reasons, with positives tending to focus on high recycling rates and the high involvement of the informal economy whilst negatives align with the city’s colossal waste volumes. To place Mexico City’s waste production in context, they sit 2nd in terms of waste produced by mega-cities globally, only behind New York [4]. They produce 20,000 tonnes per day, enough to fill their famous Azteca stadium’s capacity in one week (pictured below).

This blog aims to take a deeper look at how this waste is managed, by analysing the waste flows in Mexico City as a whole, and subsequently looking at the waste flows in the low-income neighbourhood of Tepito.

Waste management in Mexico City

The federal government in Mexico set laws surrounding waste management, but the actual waste management infrastructure is the responsibility of individual regional governments. Mexico City’s government is in charge of critical disposal sites such as landfill sites and recycling centres [5]. To go down a government hierarchical level again, each municipality (borough) in Mexico City is responsible for waste transportation and collection of waste to the aforementioned disposal sites. Although this all seems relatively straight forward and organised, in practicality the government does not really have a great deal of control over waste management. The main reason being the strength of private and informal waste collection. The informal sector is made up predominantly of waste pickers known as pepenadores who search through waste for recyclables which they then sell on. The informal workers manage the waste in tandem with the public and private sectors, however this does mean that there is no formal record of the informal worker’s contribution to waste management[6].

Tepito informality

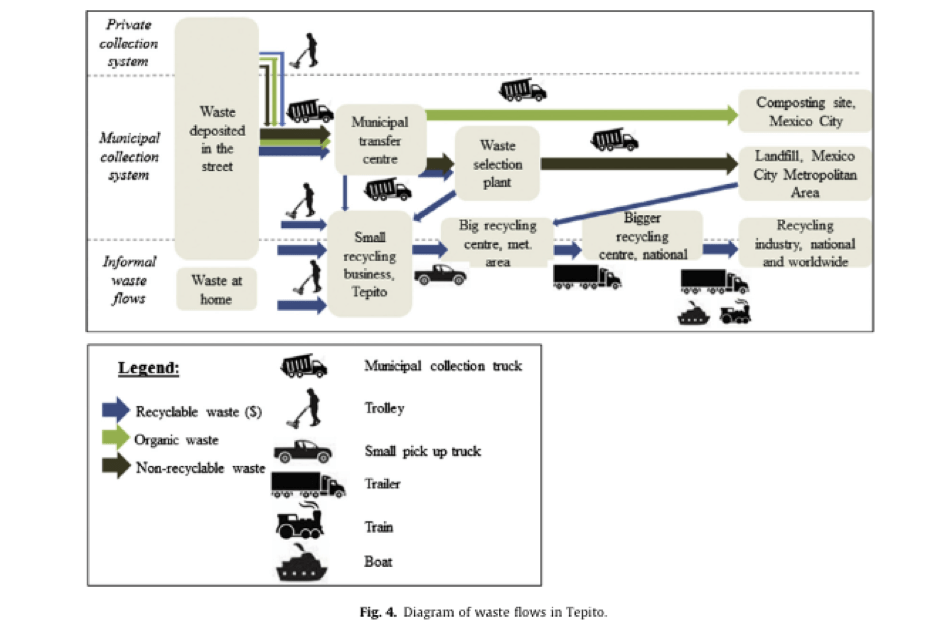

In a form of collective agency, informal waste pickers in Tepito live off the money made from selling recyclable items to the recyclable industry found in commercial and household waste. This is where the idea of the ‘circular economy’ I mentioned earlier is particularly relevant. For many this gives people are chance to earn money which they couldn’t otherwise do in the formal sector due to a host of reasons such as a criminal record for example. These waste pickers are giving value to items which seemingly to most typical members of the population have no value [7]. See the below graphic showing the waste flows in Tepito.

The way waste is managed is incredibly intricate, and the system would not work with the removal of one of these actors. Despite the value that these informal workers hold in waste management, they are not recognised at all in government waste strategies. One paper theorises that this because the government do not want any responsibilty to the informal workers and that they do not want to disrupt the cacique-based system which holds political influence steming from local chiefs. The whole informal sector involved in waste management in Tepito is essentially self regulated by “local practices of clientelism” – historic practices.

If this topic interests you, especially in the South American context, then you will find this a relevant paper by Sarah Moore. Situated in the Southern Mexican city of Oaxaca the focus is all on the politics of garbage. Likewise, if you want to find out more about the ‘circular economy’ then this 3 minute clip helps illustrate its potential:

Here are the references I used:

[1]Guibrunet, L., Calvet, M.S. and Broto, V.C., (2017) ‘Flows, system boundaries and the politics of urban metabolism: Waste management in Mexico City and Santiago de Chile,’ Geoforum, 85, pp.353-367.

[2] Cabrera, Y. (2020) ‘Lations Are Super Green. When Will Environmental Groups Realize?’, (WWW) Mother Jones: Na (www.motherjones.com – accessed 12/02/2020).

[3] Calvas, V. (2020) ‘Waste pickers under threat’, (WWW) Ecologist: N/a (www.theecologist.org – accessed 12/02/2020).

[4] WOIMA (n/d) ‘Drowning in Waste – Case Mexico City, Mexico’, (WWW) WOIMA: N/a (www.woimacorporation.com -accessed 12/02/2020).

[5] Guibrunet, L., Calvet, M.S. and Broto, V.C., (2017) ‘Flows, system boundaries and the politics of urban metabolism: Waste management in Mexico City and Santiago de Chile,’ Geoforum, 85, pp.353-367.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

This is a really interesting example of how informal means of waste management are central to the overall system in Mexico City. The pepenadores are very reflective of the catadores, the focus of my blog posts on the informal circulations of waste across Rio. I wonder, do these means of waste circulation show how waste materials are imagined differently by various agents in the process? Sure, the municipal governments responsible are keen to present themselves as sustainable, but do you think there could be an overall shift in how waste is managed by formal means and could be better than the status quo?

LikeLike