One of the ecological priorities for Montreal seems to be revegetation (verdissement in Quebec French), principally to struggle against heat island effects but also to boost biodiversity and make the city more pleasant and beautiful.

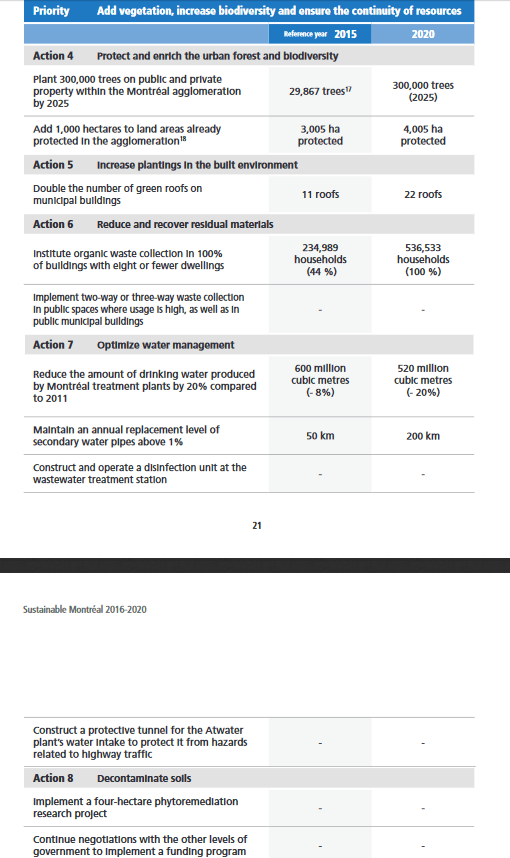

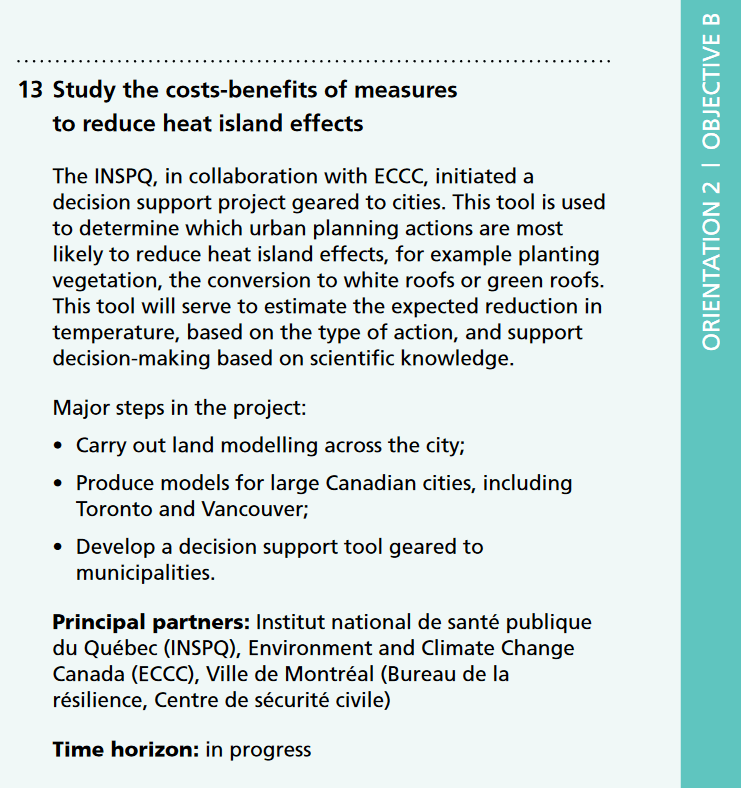

This goal appears in several official documents. In Montreal’s last sustainable plan for the period 2016-2020, one of the four priority for action is ‘add vegetation, increase biodiversity and ensure the continuity of resources’ with the action 4 and 5 that concern revegetation (Ville de Montréal, 2016). The point 1.16 of the program of Valérie Plante, elected in 2017, is ‘green the city and reduce “heat islands”’ (Projet Montreal, 2017) . The action 13 in the Montreal’s Resilient City Strategy published in 2018 is ‘study the cost-benefits of measures to reduce heat-island effects’ to ‘determine which urban planning actions are most likely to reduce heat island effects, for example planting vegetation’ (Ville de Montréal, 2018).

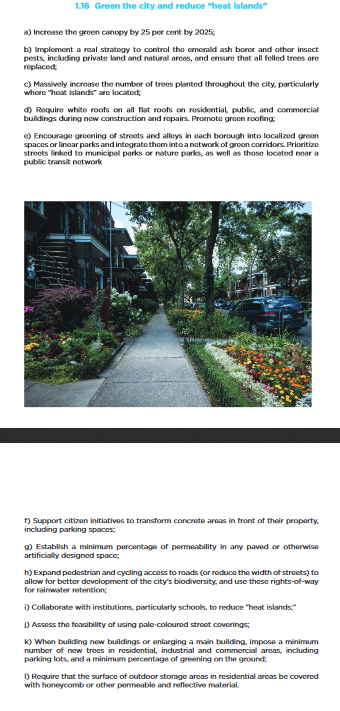

An article of Yupeng Wang and Hashem Akbari called ‘Analysis of urban heat island phenomenon and mitigation solutions evaluation for Montreal’ starts with explaining what are urban heat island (UHI). They explain that cities are warmer than rural areas because urban surfaces are darker, there is less vegetation and buildings and street surfaces materials store heat during the day before releasing it at night (Wang & Akbari, 2016, p. 438). They consider that urban tree planting provides a more pleasant place to live and contribute to well being while the absence of vegetation impacts UHIs because trees intercept solar energy and reduce temperature of surface below with their shades (Wang & Akbari, 2016, p.439). They talk of other UHI mitigation options than tree planting. It can be other form of revegetation such as green roofs or increases in albedo with light coloured roofs and pavements. In their study of a small area of Montreal, they notice that granite paving have higher albedo than asphalt but higher heat capacity and heat absorption that negate at night the positive effect of albedo during the day. Nevertheless it is a question of material properties and increasing light coloured surfaces to increase albedo seems to be relevant. The point 1.16 of Valérie Plante’s program indicates that she would encourage white and green roofs. She would like to assess the feasibility of using pale-coloured street coverings, whose reflexivity is presented by YupengWang and Hashem Akbari also as a safety factor by increasing visibility (Wang & Akbari, 2016, p. 445).

If reducing heat islands is one of the major environmental positive impact of revegetation, it is not the only one. It participates to the protection of biodiversity with the creation of new habitats. It captures carbon, that is not released in the atmosphere and does not participate to global warming. It also captures some air pollutants. Shannon Gourdji in her article ‘review of plants to mitigate particulate matter, ozone as well as nitrogen dioxide air pollutants and applicable recommendation for green roofs in Montreal, Quebec’ tries to identify what are the best plants to remove different major air pollutants in the city. Shannon Gourdji notices that specific species of small conifers are efficient for particulate matter pollution, Japanese maple for 03 pollution and magnolia for N02 and indirectly 03 pollutions (Gourdji, 2018, p. 385-386)

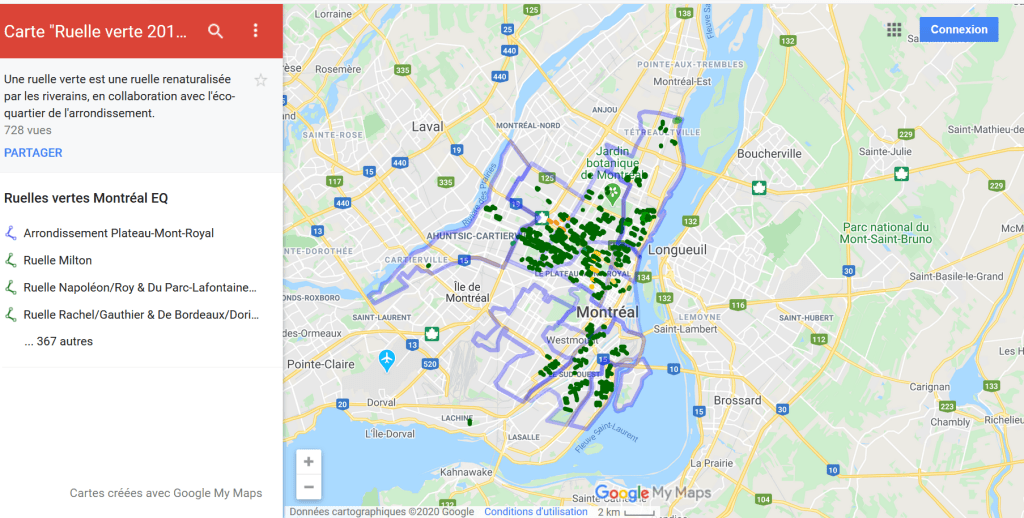

Montreal’s revegetation can take different forms. It can be for example street planting organised by the municipality, public or private green roofs and parks. Montreal have also lots of projects of ‘ruelles vertes’ (green alley, street) which are collective projects made by citizens with the support of borough to transform their alley. They implemente vegetation to create pleasant places and social links while it reduces heat islands. Montreal’s urbanisation between the end of the 19th century and the middle of the 20th century was made around large streets and small alleys between them at the back of buildings. Since about 20 years, some of them are redesigned in ‘ruelles vertes’, with a new craze for a few years. A website made by the non-profit organisation Regroupement des éco-quartiers (REQ) explains how to start your project of ‘ruelles vertes’.

An example of ‘ruelle verte‘ in Montréal, source: REQ

Another important part of urban revegetation lies in urban agriculture that we did not address in this post. I think that it will be the topic of one of the next posts because Montreal seems to be dynamic in this domain.

References

Gourdji, S. (2018). Review of plants to mitigate particulate matter, ozone as well as nitrogen dioxide air pollutants and applicable recommendations for green roofs in Montreal, Quebec. Environmental Pollution, 241, 378-387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.053

Projet Montreal. (2017). Program 2017 Valérie Plante. Retrieved from https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/projetmontreal/pages/1996/attachments/original/1506701286/program2017_EN.pdf?1506701286

Regroupement des éco-quartiers. (2020). Ruellesvertesdemontreal.ca. Retrieved 7 March 2020, from https://www.ruellesvertesdemontreal.ca/.

Ville de Montréal. (2016). Sustainable Montréal 2016-2020, together for a sustainable metropolis. Retrieved from http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/pls/portal/docs/page/d_durable_en/media/documents/plan_de_dd_en_lr.pdf

Ville de Montréal. (2018). Montréal’s Resilient City Strategy. Retrieved from http://www.100resilientcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/MTL_Strategie_montrealaise_ville_resiliente_en_lr.pdf

Ville de Montréal – Propreté – Ruelles vertes. Ville.montreal.qc.ca. (2020). Retrieved 7 March 2020, from http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=9257%2C143268832&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL.

Wang, Y., & Akbari, H. (2016). Analysis of urban heat island phenomenon and mitigation solutions evaluation for Montreal. Sustainable Cities And Society, 26, 438-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2016.04.015

I had never previously come across urban susceptibility to heat, so thanks for sharing this innovative piece. It seems as though vegetation in the city has multiple benefits: reducing urban heat island effect, extracting pollutants and creating cleaner air. How is this approach to urban design/planning not more popular?

I also wonder if the distribution map you included is considered even, or do the ‘ruelle vertes’ concentrate in more privileged areas in the city? Access to nature should be a basic human right, with plenty of literature discussing our evolutionary ties and the benefits it has on our mental and physical wellbeing. I look forward to reading your piece on how Montreal is embedding agriculture into its urban domain.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment.

I don’t know. I think this approach is gainning progressively popularity in most big cities for new developments and renovation. Put more vegetation in streets imposes constraints concerning maintenance, traffic or public events hosting that have to be considered. Things need time to be implemented. Nevertheless, I think things can move more quickly, notably with the support of citizens’ initiatives, and that things have to move faster in regards to the climate emergency.

I think revegetation with urban agriculture has even more benefits, both social and ecological.

LikeLike